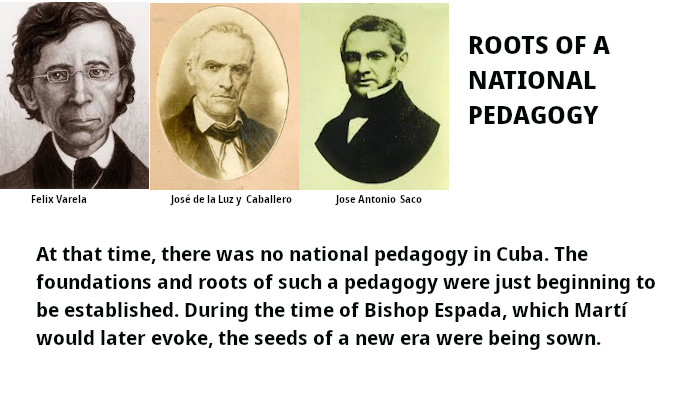

By the late 18th century, new currents of thought began to take shape in Cuba, challenging the entrenched slaveholding and colonialist norms that dominated the island. Leading figures such as Félix Varela, José de la Luz y Caballero, and José Antonio Saco spearheaded this liberating movement, firmly rejecting an ideology rooted in the values of sugar and coffee commerce.

In 1793, the Cuban Academy of Literature was established under the Education Section of the Economic Society of Friends of the Country, though its true purpose was to reinforce ties with Spain, the so‑called Motherland.

At that time, Cuba lacked a national pedagogy. Its foundations were only beginning to emerge. Under Bishop Espada — later evoked by Martí — seeds of renewal were sown. From the San Carlos Seminary, with its chairs in Philosophy, Constitution, and Economics, modern ideas began to nurture a liberating vision of Cuban society and sketch the outlines of its destiny.

Father Varela championed the social knowledge of the people, dismissed by the slaveholding elites. He condemned the arrogance of philosophers absorbed in abstract speculation, indifferent to the realities of the nation. He denounced inconsistency, improvisation, the devaluation of labor, blind imitation, and the pursuit of wealth without substance — all hallmarks of Cuban society at the time. Thus, the 19th century began to shape a pedagogy grounded in ethical principles, distinct from the failed models of education under slavery.

The Economic Society of Friends of the Country, guardian of early Cuban historical writings, promoted the idea of a national history — as Bishop Morel de Santa Cruz had proposed — in step with the growing awareness of Cuban identity.

In the philosophical debates of the late 1830s, Varela sought to ensure that teaching was not stagnant or merely justificatory, but critical and constructive, aimed at transforming human and social nature. He underscored the importance of historical thought and challenged the intellectual elites, whose scholarship often served profit, class legitimacy, and cultural dominance.

Luz y Caballero envisioned a renewed spirituality for Cuba, engaging in discussions on morality, science, and religion, aware that literature, ideology, and psychology could either strengthen or weaken the emerging nation. Martí honored him as the Founding Father, recognizing his ability to touch the essence of things — “to see the flower in the wound.” His aphorisms alone sufficed.

For Martí, everything was unity: science, homeland, consciousness, culture, politics. His phrase “Cuba is the homeland of La Luz and Varela” captured this synthesis. Living among the people was his true school. He thought deeply, like his predecessors, and transcended the failures of independence in a fractured Republic, where pedagogy became central to shaping the nation’s cultural values.

This pedagogy drew from global educational movements while remaining rooted in Cuba’s philosophical and pedagogical tradition. Even amid imitation and subjugation to foreign ideas, critique persisted — from psychological theories to reflections on the formation of national cultural values.