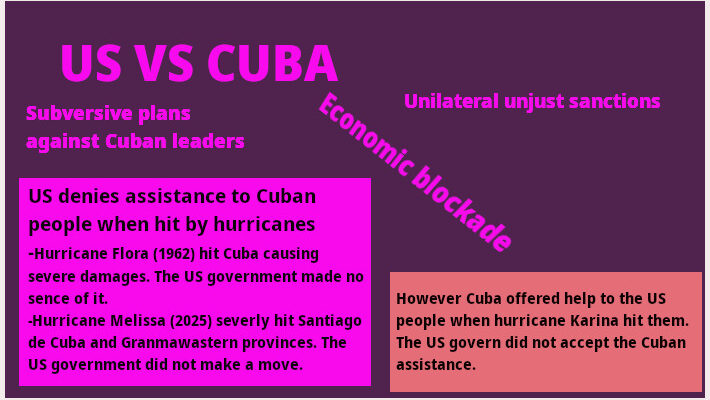

US policy towards Cuba after 1959 has that of aggression and constant hostility in all fields of the political, social economic life of the island. They have forgotten the roots of their Independence War. They simply disregard humanitarianism, even when natural events have hit severely Cuba.

When hurricanes strike Cuba, the human and material toll can be severe: damaged homes, flooded streets, lost crops, and disrupted services. In many disaster-prone nations, international assistance flows quickly to help with search and rescue, emergency shelter, food, medicine, and the early stages of rebuilding. In the case of Cuba, however, US government assistance is often withheld or limited, a policy rooted in decades of political tension between the two countries. That refusal shapes both the immediate humanitarian response and longer-term recovery.

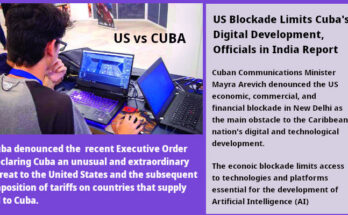

Historical and political context US–Cuba relations have been shaped by Cold War-era hostilities, a longstanding economic embargo, and varying diplomatic openings and closures. Even when diplomatic ties briefly warmed, such as during the 2014–2016 rapprochement, broader legal and political barriers to direct US government aid remained.

Sanctions laws, restrictions on bilateral programs, and congressional limits complicate or prevent direct transfers of government disaster assistance to Cuba. This legal framework reflects political decisions in Washington as well as domestic constituencies that oppose easing ties without broader policy changes in Havana.

Such were the ase of hurricanes Flora in 1962 and Melissa in 2025, just to mention two of them. When US government aid is unavailable, the immediate practical effect can be slower or reduced access to resources that might otherwise help save lives and reduce suffering.

Cuba maintains a robust civil defense system and a long history of disaster preparedness that mitigates some impacts: early evacuations, state-run shelters, and centralized emergency coordination help limit casualties. Still, large storms can overwhelm capacities—especially in poor, rural, and coastal areas—leaving vulnerable populations exposed to prolonged shortages of clean water, medicine, shelter, and power.

Alternative aid channels Although direct US government assistance is often denied, aid still reaches Cuba through alternative routes. Private US charities and faith-based organizations sometimes provide relief, though they face regulatory hurdles and limits under the embargo. International organizations, regional partners, and multilateral agencies can coordinate and fund relief that benefits Cubans.

Neighboring countries and NGOs also play roles, sending supplies, technical teams, and financial help. These channels can be slower or smaller in scale than bilateral government-to-government aid, but they do provide crucial support.

Practical and ethical considerations The refusal of direct US aid raises practical questions about the best way to reduce human suffering. From a practical standpoint, humanitarian assistance is usually most effective when delivered quickly and at scale; government-to-government aid can facilitate that.

Ethically, many argue that disasters should transcend politics and that populations in need deserve rapid help regardless of bilateral disputes. Policymakers face a tension between strategic objectives—pressuring governments through sanctions—and immediate human costs in disaster settings.