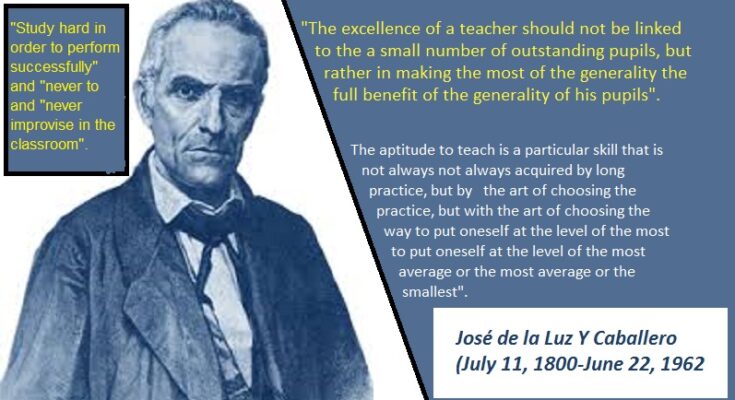

Cuba is what it is, an independent and sovereign nation, not because of luck or random chance. This is the result of our forefathers, as José de la Luz y Caballero (July 11, 1800-June 22, 1862), who a part from his job as a professor, was also a philosopher and a revolutionary methodologist.

At the age of twelve, José de la Luz was already studying Latin and philosophy in the convent of San Francisco. In 1817 he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the Royal and Pontifical University of San Geronimo in Havana. Some time later, personal inclinations and the wishes of his mother and uncle made him begin a career common to many of the offspring of wealthy Creole homes of the time, the priesthood. He then entered the Seminary College of San Carlos and San Ambrosio.

At the Seminary of San Carlos he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Law. There he met Félix Varela y Morales, from whom he received classes as well as from his uncle José Agustín. It is precisely in these years, and through his experiences in the Seminary and his studies of the doctrines of those encyclopedic masters, that he deepens his proximity to the renovating scientific spirit of the European eighteenth century, studying European philosophers such as Locke, Condillac, Rousseau, Newton and Descartes. He also adheres to the struggles of Varela and Caballero against philosophy and the scholastic teaching methods enthroned in the subjects and pedagogical plans of the Seminary and all the educational centers of the capital, and is linked to the cultural, scientific and civic efforts of Bishop Espada.

He mastered languages such as English, French, Italian, German, and in 1821 he translated the work of the Count of Volney. He traveled in Egypt and Syria during the years 1783-1785.

His knowledge of theology and religious life led him to speak out repeatedly against the Spanish clergy residing in Cuba. Perhaps it was these convictions that distanced him from the religious cloister and already in 1824 we find him as director of the Chair of Philosophy of the Seminary of San Carlos, to which he gains access by means of tests of opposition. Previously, this responsibility had fallen into the hands of José Antonio Saco, a fellow disciple and close friend of Luz, as well as into those of the professor Varela, his creator.

From the beginning of his activity as Director of the Chair of Philosophy, he was determined to apply the knowledge and ideas of his professor, Félix Varela, in depth and to their ultimate consequences. He became famous not only among his admirers, but also among his detractors, for his fidelity to the methodology and doctrines of Varela, whom, according to his own words, he quoted almost daily and by whose texts he was guided to teach his classes.

During his life he used several pseudonyms, among them: “Un Habanero”, “El Justiciero”, “Un Amante de la Verdad” and “El Amigo de la Juventud”.

He died in Havana on June 22, 1862. His death caused general consternation in the country, and there were demonstrations of grief for the misfortune, throughout the island schools were closed for three days as a sign of mourning.

As an educator, for many his most outstanding activity, he held the position of Director of the Colegio de San Cristóbal, where he requested a license to inaugurate a Chair of Chemistry, and offered a course in Philosophy, between 1834 and 1835. He founded the Colegio del Salvador, in January 1848, recognized at that time for the implementation of modern teaching methods, in which he made his private library available to students and teachers; there special classes in Philosophy, German and Latin were given to the most outstanding students, he tried to include the most advanced in science with the use of modern methods of research, and tried to instill in his disciples a sense of human elevation.

The duty of the teacher was, for him, to habituate the pupils to think by themselves. In both schools he published annual pamphlets with the general examinations. He also presented a project for the creation of a Cuban Institute, a kind of practical school of science, which he was unable to turn into reality. His pedagogical conception considered that the starting point of knowledge was experience and observation, and that the experimental method, besides being the only productive one, was also the only truly analytical method that could be called scientific.

His conception of the progressive European thought of the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries was essentially related to thinkers of the philosophical stature of Descartes, Bacon, Newton, Locke, the French Enlightenment in general, and Condillac in particular. Several philosophical polemics had him as a protagonist, facing figures of the stature of Domingo del Monte, Presbyter Francisco Ruiz, Manuel Costales and the brothers Manuel and José Zacarías González del Valle. He also polemicized with Pedro Alejandro Auber on Mathematics problems (1832-1833).