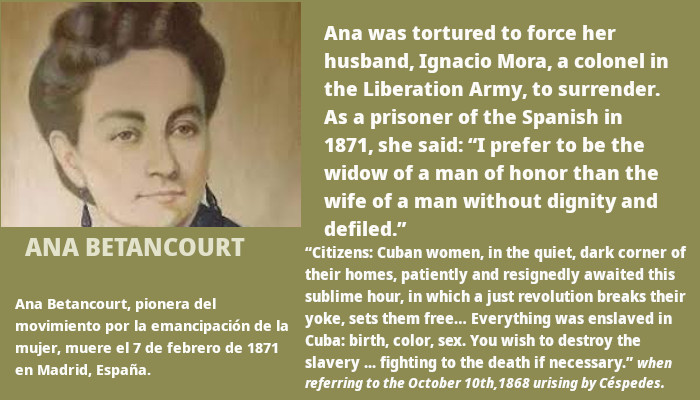

Ana Betancourt (1814–1877) emerges as a pioneering and articulate advocate for women’s rights in Cuba. Born into a prosperous landowning family in Bayamo, in the former Oriente province, she matured during a period marked by colonial rule and social upheaval. Rather than embracing the comfortable life her background could have provided, Betancourt actively participated in the struggle for independence, using her public platform to advocate for both national liberation and enhanced dignity and opportunities for women.

Betancourt married Juan Manuel Sánchez Agramonte, a fellow criollo who shared her republican and reformist ideals. When the Ten Years’ War for Cuban independence commenced in 1868, the couple openly supported the uprising. Their home became a hub for revolutionary activity in eastern Cuba, with Betancourt assuming organizational and moral leadership roles. Arrested by Spanish authorities alongside her husband in 1869, she refused to accept exile or silence. Instead, Betancourt transformed personal sacrifice into political action, using her imprisonment and subsequent exile to amplify her ideas.

Betancourt’s most renowned contribution is her public speech, “The Protest of a Cuban Woman” (Protesta de una Cubana), delivered in 1869. Addressed to the Assembly of Guáimaro, which was deliberating the future political organization of the insurgent movement, the speech is distinguished by its courage and clarity. In it, Betancourt asserted that the fight for independence must encompass social and legal reforms recognizing women as full citizens, not merely auxiliaries to male revolutionaries.

She argued that women had already contributed decisively to the independence effort—as nurses, fundraisers, messengers, and even combatants—and deserved rights commensurate with their sacrifices. Betancourt called for the abolition of legal disabilities that left women dependent on fathers or husbands, for access to education, and for moral recognition of women’s capacity for civic judgment. Her tone blended moral suasion with practical demands: securing women’s legal and economic autonomy would strengthen the nation as it emerged from colonial rule.

Influence and legacy At the time, Betancourt’s proposals were radical. The revolutionary leadership, though grateful for women’s contributions, generally saw gender issues as secondary to the larger military and political struggle. Still, her words left a mark. “The Protest of a Cuban Woman” circulated among activists and later feminist thinkers, becoming a touchstone for debates about citizenship and gender in Cuba.

Betancourt’s life also symbolized the moral commitment of many women in the independence movement. She endured exile and separation from family rather than renounce her convictions. After the war, although she did not live to see an independent Cuba, her example inspired subsequent generations of activists who linked national liberation with social reform. Cuban women in the early twentieth century, campaigning for suffrage and legal rights, frequently invoked Betancourt’s legacy.

Why she matters today Ana Betancourt’s importance lies in the intersection of national and gender politics. She anticipated modern feminist arguments that political freedom is incomplete without social and legal equality. Her insistence that women be recognized as active citizens—worthy of education, economic agency, and legal protection—remains relevant in ongoing global conversations about gender and citizenship.

Her life also offers a broader lesson about the role of conscience in political struggle. Betancourt refused to be a silent supporter behind the scenes; she demanded that movements aiming to create a freer society also live up to their declared ideals. That insistence—combining patriotic fervor with a clear-eyed critique of internal inequalities—marks her as a pioneering voice worth remembering.

Further reading and sources For readers who wish to explore Betancourt’s writings and historical context, look for collections on Cuban independence and nineteenth-century Caribbean women’s activism. Translations and analyses of “The Protest of a Cuban Woman” appear in studies of Latin American feminist thought, and biographical essays place her life within the broader currents of the Ten Years’ War and Cuban social history.