Early in 1878, Máximo Gómez wrote in his War Diary: “A complete demoralization is noticeable and everyone is in low spirits, as much by the constant operations of the enemy as by the division of the Cubans”.

The Revolution was without leadership because Tomás Estrada Palma, president of the Republic in Arms, was betrayed and arrested and his substitute, Francisco Javier de Céspedes, had resigned, as Gómez himself did as Secretary of War, while the tendency to surrender was gaining ground among many chiefs of the center and eastern provinces.

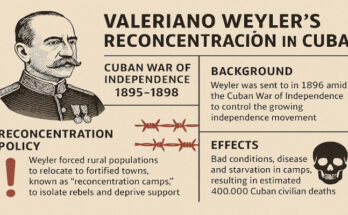

The most immediate antecedents of that situation dated back to mid 1876, with the arrival in Cuba of Captain General Arsenio Martinez Campos with 20 battalions of infantry, cavalry and artillery, which increased to more than 100,000 the number of colonial troops.

However, the Spanish chief achieve no glory in the battles against the Cubans, neither in that conflict nor in the war of 1895, but he was a clever and skillful soldier who had been nicknamed El Pastelero (The pastry cook) for his capacity for compromises and negotiations, which he also used in Cuba due to the lack of resources and supplies among the pro-independence fighters.

Thus he contacted many, mostly well-to-do chiefs who had lost their assets in the war to propose peace, integration and economic compensation, but neither independence nor abolition of slavery, and managed to convince many of them who were already tired of fighting.

In February 1878, a number of mambí leaders approved by General Martínez Campos signed an agreement known as the Zanjón Pact, the terms of which the Spanish would report to Antonio Maceo, the most important Cuban leader, who was still fighting Spain.

Confident of his success and with the conditions of the Pact in his horse’s saddlebag, Martínez Campos traveled to Mangos de Baraguá, in eastern Cuba, to meet with Maceo, oblivious to the moral stature of that mulatto of humble origin who would spoil his colonialist plans for Cuba that day, March 15, 1878.

The Spaniard’s tactic was to impress Maceo with his speech, recognize his sacrifice but call it useless, extol a dignified peace with Spain in exchange for dubious promises of reforms and, finally, ask him to sign the Zanjón Pact, but the Cuban soon voiced his disagreement with the treaty and his decision to continue the fight until Cuba was free and slavery abolished.

Disconcerted, the Captain General could only agree to the resumption of hostilities within eight days so that the troops could return to their respective regions. Even if Maceo and his troops could hardly keep fighting, the Cuban made it clear that the true patriots would not give up the independence ideal for which they had fought for 10 years.

The Bronze Titan’s feat saved the Revolution from that trap of a spurious peace and made possible the “fruitful truce” that followed in 1878, during which José Martí prepared and launched the Necessary War of 1895-1898.

The Protest of Baraguá, considered an example of revolutionary resistance and intransigence, was described by Martí as “one of the most glorious in our history”.

(Taken from ACN)