On February 24, 1895, the struggle against Spanish colonialism resumed in Cuba, a necessary war, as Martí called it, after an intense struggle by Cubans inside and outside the island, and after facing the failure of the Fernandina Plan.

At the beginning of 1895 there was in Cuba an evidently insurrectionary atmosphere. In the years 1893 and 1894, José Martí, the maximum organizer of this gesture, toured several countries of America and cities of the United States, to unite the main leaders of the War of ’68 among them and with the youngest ones, besides gathering resources for the new struggle.

Since the middle of 1894, he accelerated the preparations of the so-called Fernandina Plan, with which he intended to promote a short war, without great wear and tear for the Cubans.

On December 8, 1894, he wrote and signed, together with Colonels Mayía Rodríguez on behalf of Máximo Gómez and Enrique Collazo on behalf of the patriots of the Island, the plan for the uprising in Cuba.

The plan was discovered by the Spanish authorities and consequently all the military and logistic material gathered was seized. In spite of the great setback that this meant, Martí decided to go ahead with the plans for armed uprisings on the Island, which was supported by all the main leaders of the previous wars and this setback, far from discouraging the independence fighters, raised the revolutionary spirit.

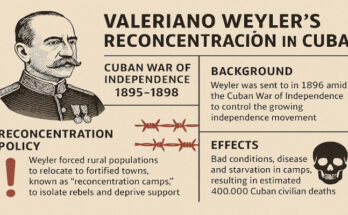

Cuba was submerged in an economic crisis, tinged by the embezzlement of the budgets and a high and iron tax policy of the Spanish crown.

On the other hand, Cubans lacked political rights, including the right to hold government positions. In this scenario, political parties opposed to Cuba’s independence appeared.

Faced with the loss of economic control, the crown increased its repression, describe notes of the time.

In that context, social ills grew, but at the same time subjective conditions were present such as the presence of José Martí as a leader, a leading force such as the Cuban Revolutionary Party, and a high consciousness of the masses that maintained their independence ideals.

The revolutionary situation that arose in 1895 in Cuba was expressed in the sharpening of the colony-metropolis contradictions.

Martí arranged a consultation of deep political significance: the election of the General in Chief of the Liberation Army, and already on August 18, 1894, the Dominican Máximo Gómez was unanimously elected.

According to scholars of that historical stage, it was a generalized opinion among the emigrants and on the Island that without the participation of the valuable warrior, the complete success of a new struggle was impossible.

Upon assuming the assignment that the Party placed in his hands, the General was in charge of an essential task of the organizational phase: he had to summon chiefs and officers who at some point had been under his orders and, with them, set in motion a military structure.

The task demanded maximum secrecy, since most of them were in enemy-occupied territory. Along the way, disagreements arose on tactical aspects and there were moments of misunderstanding, but all difficulties were smoothed out by the strength of shared principles.

The war broke out on February 24, 1895 and although many historians assure that it began in the town of Baire, -that is why it is always remembered as the Grito de Baire-, other experts affirm that the uprising occurred simultaneously in several points of the national geography.

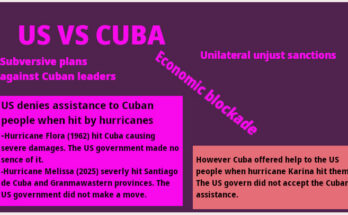

This feat -although superior in several aspects to the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878)- had once again the misfortune of repeating the mistakes of that campaign, such as the lack of unity among the military chiefs, something that the United States took advantage of.

The absence of consensus among the leaders of the campaign made it possible for the North American country to find a gap to annihilate the representative bodies of the Cuban nation. It also added the loss of unifying political-military leaders such as Antonio Maceo and José Martí, who perished on the battlefield.

The United States contemplated the struggle of the Cuban people for 30 years, and put its determination to take over the largest of the Antilles and made it clear when it prevented the entry of the Mambi troops (insurrectionists) to Santiago de Cuba and with the Treaty of Paris, which put an end to the so-called Spanish-Cuban-American war.

Nevertheless, the restart of the war on February 24, 1895 and its entire trajectory served as a lesson for later times from the political-military point of view, especially in terms of the need for a single command.

On the other hand, many became aware that the predictions of the Maestro, as Martí is also known, were valid for Cuba and the rest of Latin America, because he knew how to understand in time the danger that the giant of the North represented for the peoples of the continent.