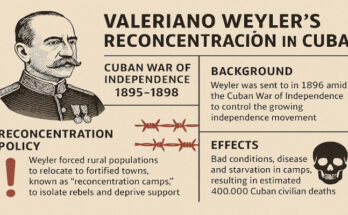

“The Cuban war rested in the sad February”. Thus José Martí sentenced the unfortunate outcome when assessing the Pact of Zanjón, expression of the Cuban arms surrender and the approval of a peace without independence and without the abolition of slavery.

This Pact, signed on February 10, 1878 between the so-called Revolutionary Committee of the Center and the Captain General of the Island Arsenio Martínez Campo, in Camagüey, was an irrefutable proof that the fracture of unity at the beginning of our independence struggles was the worst enemy of the revolutionary process.

Undoubtedly, the bases approved in that document were so ambiguous and so cunningly written by the Spanish side, that what was granted to Cuba was nothing, or so little, that it was almost a mockery, beyond how disastrous it would be for the subsequent course of the wars of independence.

Cuba was granted the same status as Puerto Rico, although it was later learned that these apparent advantages referred only to the electoral system and the territorial management. Cuba was called to forget the past under the premise of unconditionally laying down their arms and accepting Spanish rule over the island.

Freedom would only be obtained by those black slaves and Chinese colonists who had served in the ranks of the Liberation Army, and Cubans would be given the possibility of creating political parties, as long as they were not contrary to the Metropolis or endangered their interests.

In good Cuban terms, what was agreed upon were crumbs. Nothing of what Carlos Manuel de Céspedes demanded in the Manifesto of October 10, nor what was approved in the Constitution of Guaimaro in April 1869 was contemplated in that Pact; it was as if the blood shed by the Father of the Homeland, Agramonte, Miguel Gerónimo Gutiérrez and other anonymous patriots, had been in vain.

A shameful pact

The signing of the shameful pact, 145 years ago, illustrated that regionalism, caudillismo, the lack of support from Cuban emigration abroad and the intelligent policy of Peacemaker Martinez Campo, were causes that ruined the wear and tear of almost 10 years of struggle, also taking advantage of the skepticism of others.

One month and five days later, on March 15, 1878, the Pact of Zanjón would find in the Protesta de Baraguá the best response to the the best of its answers with General Antonio Maceo as its architect. architect.

If in that historic event the sword had been dropped sword was dropped, as Martí judged, in Baraguá the sullied honor would be saved and the the sullied honor and would reaffirm the Cuban ideal of continuing to fight for the independence of Cuba and the abolition of slavery.